A patient’s age-related macular degeneration (AMD) at any stage should rise to a high level of importance for optometrists. Imaging is important to feel optometrists confident in their diagnosis, says Jessica Haynes, OD, with the Charles Retina Institute in Germantown, Tennessee. “We know from literature that AMD is generally underdiagnosed even with a dilated eye examination1,” she says. That is where the dominos begin to fall.

“From my personal experience, I believe that not only are we not diagnosing AMD, but in general we are not staging it appropriately when we do make the diagnosis. Even patients with advanced stage AMD (particularly those with geographic atrophy or GA) are told that that they have ‘just a little bit of AMD.’”

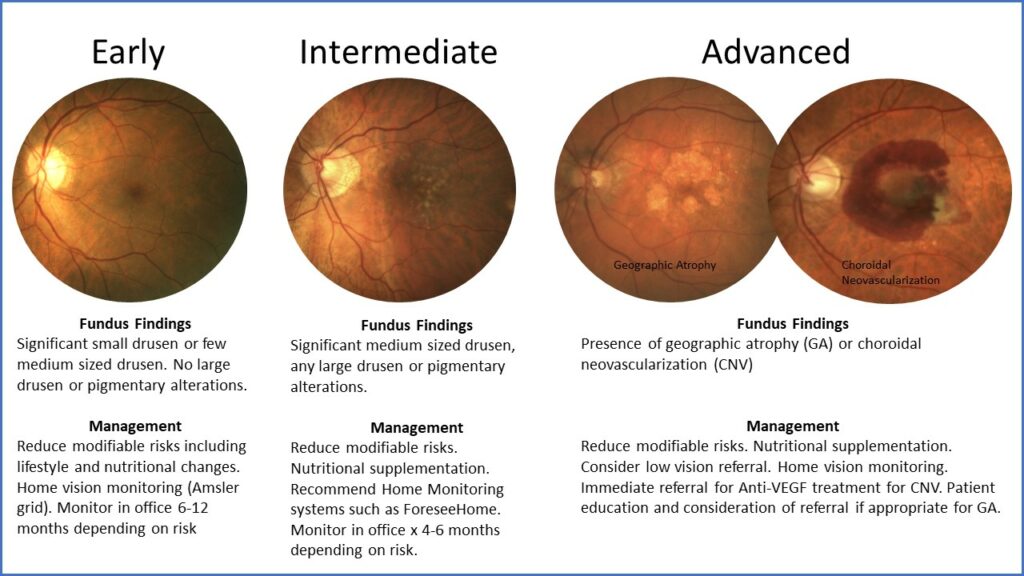

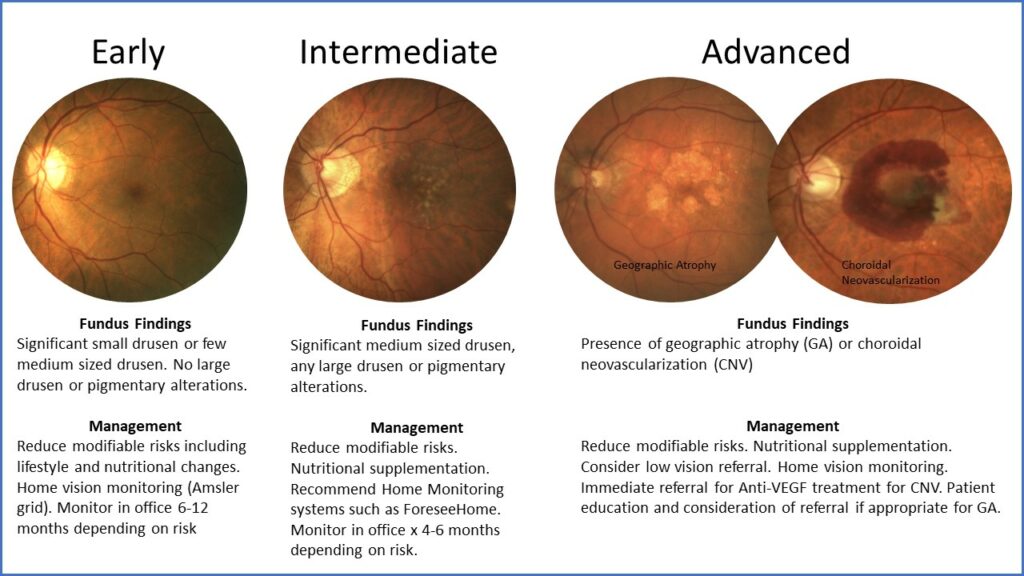

Dr. Haynes says that primary eye care providers must identify patients with any stage of AMD so that these patients can begin lifestyle and health modifications to reduce their risk. “It is so important to identify those with intermediate stage AMD, such as those with either large sized drusen over 125 microns or those with pigmentary changes. Then we can discuss appropriate vitamin supplementation with them and monitor them more carefully as these are patients who have higher risk to develop advanced disease. And it is more crucial now than ever to identify those with advanced stage AMD so that they can be appropriately educated and referred,” she says.

The key is imaging. Imaging can help ODs identify those with AMD, stage it more appropriately and identify those who are at most risk to develop advanced stage disease by looking for high-risk biomarkers on the optical coherence tomography (OCT), fundus autofluorescence (FAF) and near infrared reflectance imaging, she says.

OCT BIOMARKERS

There are key OCT biomarkers that Dr. Haynes looks for.

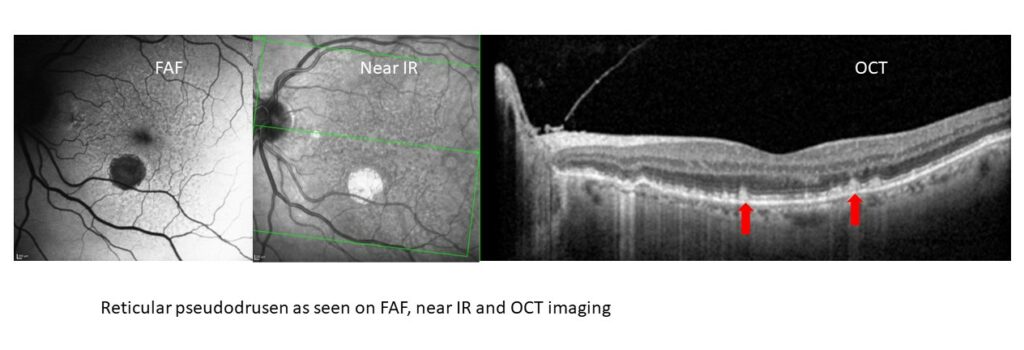

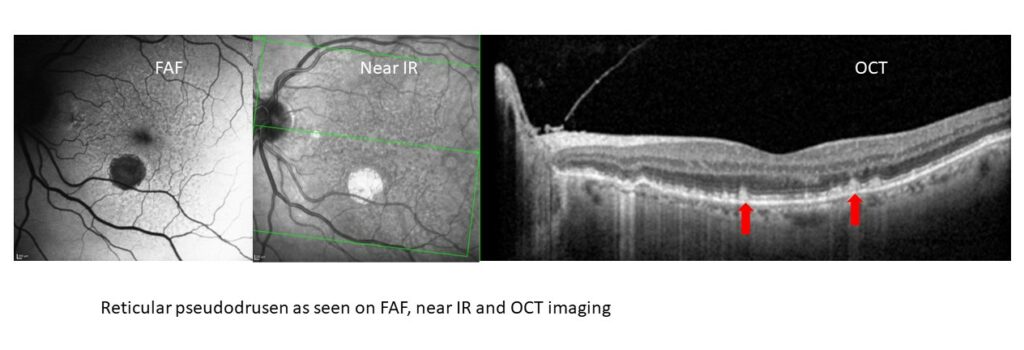

Reticular pseudodrusen (RPD – also known as subretinal drusenoid deposits)

This phenotype of drusen is very difficult to identify clinically but is seen clearly with imaging, she says. “On OCT, RPD are seen as small hyper-reflective projections that sit on top of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). On FAF and near infrared reflectance imaging, these will be seen as small circular deposits that exist in a reticular pattern.”

This is an important biomarker to identify because patients with RPD are at a high risk to develop advanced stage AMD, particularly through the formation of GA. “They also tend to have worse visual function, such as poorer contrast sensitivity, and worse dark adaptation. Despite this, clinically, they may not appear to have large sized drusen or a heavy drusen load,” she says.

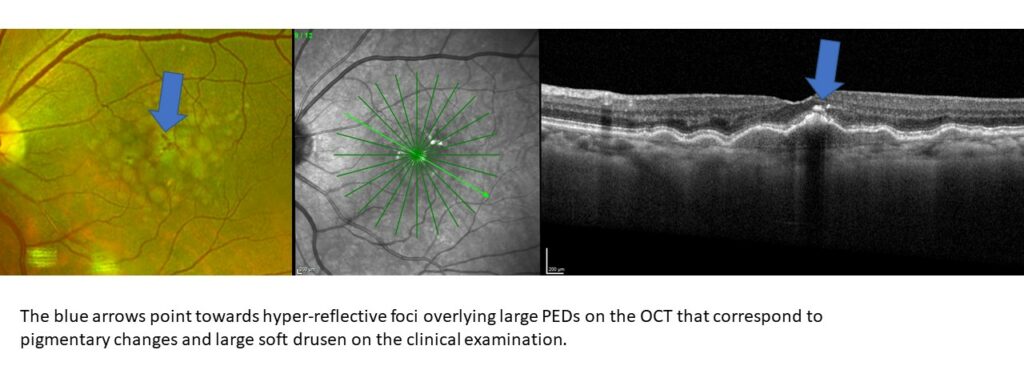

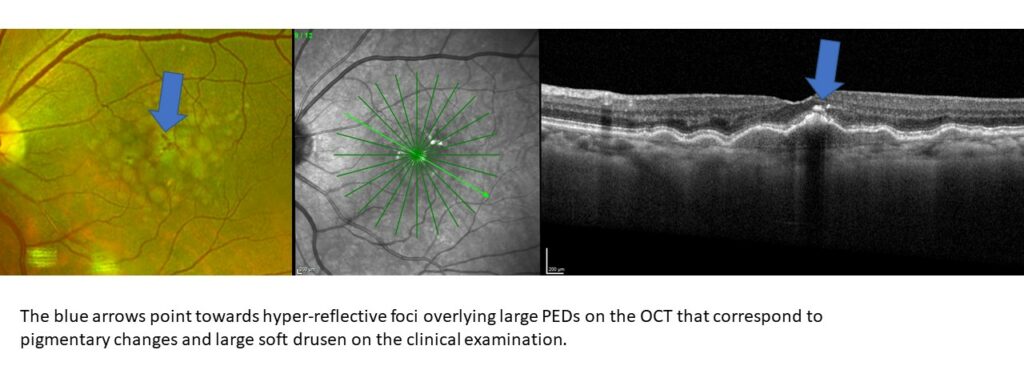

Hyper-reflective foci

Hyper-reflective foci are hyper-reflective focal deposits typically in the outer retina often seen overlying large pigment epithelial detachments. These represent pigmentary migrations from the RPE and a more diseased and irregular RPE. Clinically these may be seen as pigmentary changes. Those with hyper-reflective foci have 5x greater chance to develop GA at two years.2

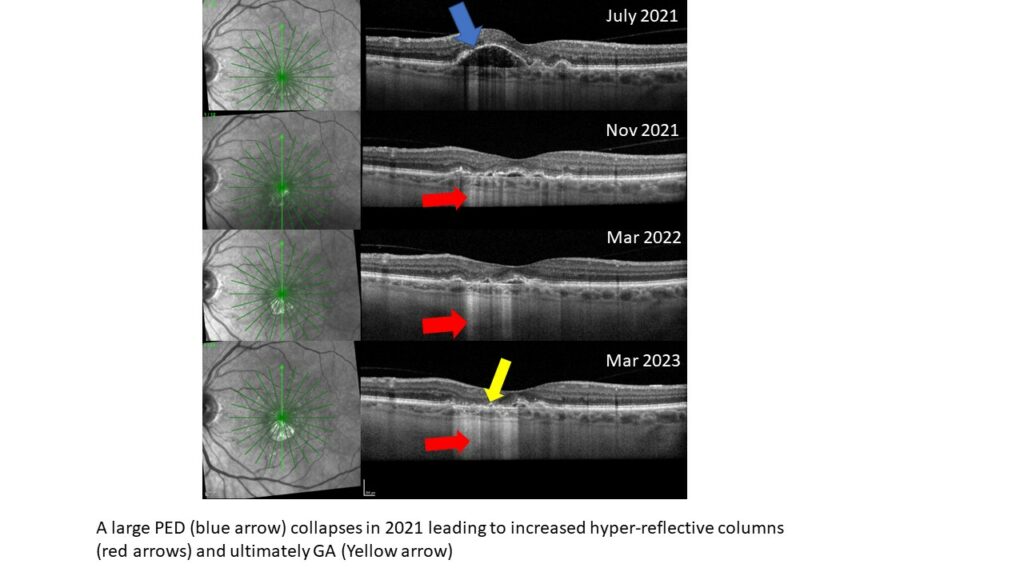

Drusen regression

The collapse of drusen or PEDs is often a precursor of GA formation, Dr. Haynes says.

Hyper-reflective columns

Hyper-reflective columns are bright regions of light that cascade beyond the RPE and into the choroid and sclera. These form as the RPE atrophies and can be indicative of a pre-GA lesion, and they are also seen in areas of GA, she explains.

AN AMD PROTOCOL: IMAGE AND STAGE

In a busy retina practice, an AMD protocol becomes increasingly important as more patients continue to present with the condition and treatment options expand. “All of my patients with AMD get an OCT, regardless of what is seen in the clinical examination, symptoms or visual acuity,” she says. But the protocol is applicable to other practices as well. “Numerous biomarkers can be identified on OCT to show risk for developing advanced stage disease. In addition, conversion to advanced disease may be seen on the OCT, especially for GA or choroidal neovascularization (CNV) that cannot be seen clinically or are not easily seen clinically,” she says.

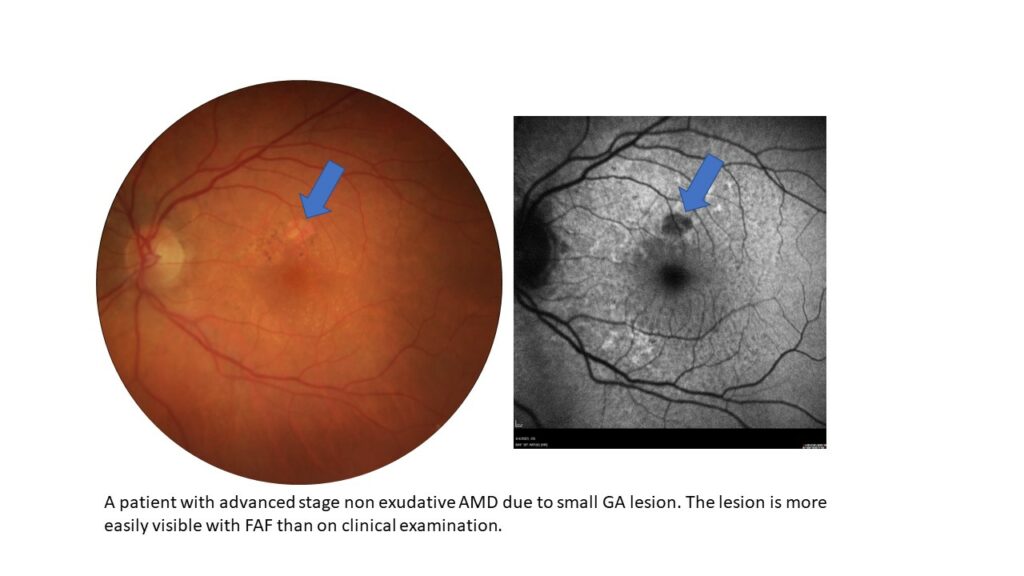

For those patients with GA, she also obtains an FAF. “This will help to delineate the size of the lesion and track the lesion over time. It will also visualize if there is hyper-autofluorescence around the GA lesion suggesting that there is higher risk of progression.”

She will also consider OCTA with those patients for whom there is concern for CNV that may not be clear on the OCT. OCTA can help her look more in-depth for CNV and particularly non-exudative CNVs.

After thorough clinical examination and appropriate imaging, patients should be staged as early, intermediate or advanced AMD and managed appropriately.

PATIENT ENGAGEMENT

Now there is more that eye care professionals can do for these patients – but more options also require more education. “With the development of two FDA approved complement inhibitors for GA, patients now have even more options and treatment decisions to wade through. Before GA therapy, treatment focused around lifestyle modifications and vitamin supplementation for those with dry AMD and intravitreal injections for those with wet AMD. For those who lost or were losing vision from GA, there was little that could be done medically, and treatment centered around low vision services,” she says.

That has changed now that there are two GA therapies approved. “While not all patients will choose to pursue these options, they must be appropriately educated to make an informed decision. Patients must understand what GA is and that GA is progressive disease, leading to loss of central visual function on average 2.5 years from diagnosis,” she says.

It’s also important to help patients manage their expectations. “These new therapies are treatments, but not cures. They slow down the progression of the disease, but they do not halt it in its tracks and they do require repeat ongoing injections with potential adverse events such increasing the risk of choroidal neovascularization.”

Dr. Haynes has found it helpful in her conversations with patients to be able to show them their imaging such as FAF imaging to demonstrate how these “blind spots” exist in their vision and perhaps show them the changes over time, if that information is available. “In addition, it is nice to have educational materials on hand to show family members how GA affects visual function even though central visual acuity may remain good.”

Yet none of those important steps can happen if primary eye care providers are not alert to the condition and actively searching for it, she says.

- Neely DC, Bray KJ, Huisingh CE, Clark ME, McGwin G, Owsley C. Prevalence of Undiagnosed Age-Related Macular Degeneration in Primary Eye Care. JAMA Ophthalmol.2017;135(6):570–575.

- Christenbury JG, Folgar FA, O’Connell R V, Chiu SJ, Farsiu S, Toth CA. Progression of intermediate age-related macular degeneration with proliferation and inner retinal migration of hyperreflective foci. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(5):1038-1045.

Read other stories about how ODs are detecting and talking with patients about GA here.

This content is independent editorial sponsored by Astellas. Astellas had no input in the development of this content. Astellas, formerly Iveric Bio.